The great debate over the length of a tweet started again with a post on the Twitter product blog yesterday and a Tweet from @Jack

We expected (and ❤️!) all the snark & critique for #280characters. Comes with the job. What matters now is we clearly show why this change is important, and prove to you all it’s better. Give us some time to learn and confirm (or challenge!) our ideas. https://t.co/qJrzzIluMw

— jack (@jack) September 27, 2017

There is a lengthy debate happening in @Jack’s Twitter post. We would LOVE to know what you think about the possible change, and its impact. Which reared its head earlier this year and was squashed with a user uproar. We are 50/50 on the change and would prefer to see more data-driven testing validation with users before a possible rollout.

- Do 240 vs 140 characters make sense or a difference in an increasingly digital attention deficit disorder driven world?

- Does the change make that big of a difference in how you express yourself or tell stories vs to distribute news?

- Does this make Twitter more like Facebook and take away from its unique signature characteristic, or add to it.

- How will it impact the way we consume content and the ROI it drives for brands using Twitter

We want to hear from you in the comments. Below is the original post with the insights from Titters product team.

Giving you more characters to express yourself

Origional Post On Twitter Product Blog By Aliza Rosen and Ikuhiro Ihara

Trying to cram your thoughts into a Tweet – we’ve all been there, and it’s a pain.

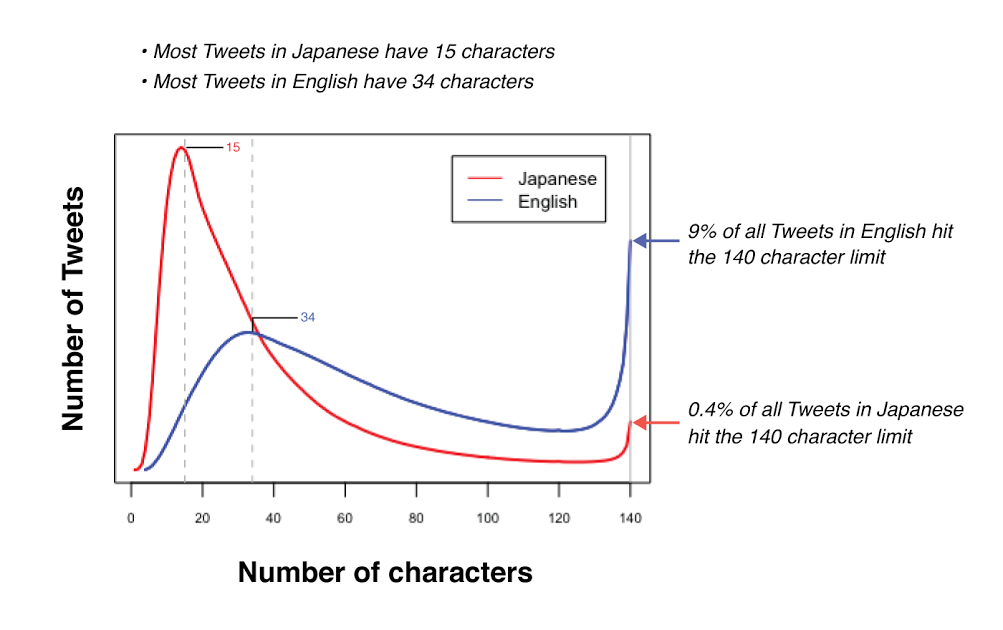

Interestingly, this isn’t a problem everywhere people Tweet. For example, when I (Aliza) Tweet in English, I quickly run into the 140 character limit and have to edit my Tweet down so it fits. Sometimes, I have to remove a word that conveys an important meaning or emotion, or I don’t send my Tweet at all. But when Iku Tweets in Japanese, he doesn’t have the same problem. He finishes sharing his thought and still has room to spare. This is because in languages like Japanese, Korean, and Chinese you can convey about double the amount of information in one character as you can in many other languages, like English, Spanish, Portuguese, or French.

We want every person around the world to easily express themselves on Twitter, so we’re doing something new: we’re going to try out a longer limit, 280 characters, in languages impacted by cramming (which is all except Japanese, Chinese, and Korean).

Although this is only available to a small group right now, we want to be transparent about why we are excited to try this. Here are some of our findings:

We see that a small percent of Tweets sent in Japanese have 140 characters (only 0.4%). But in English, a much higher percentage of Tweets have 140 characters (9%). Most Japanese Tweets are 15 characters while most English Tweets are 34. Our research shows us that the character limit is a major cause of frustration for people Tweeting in English, but it is not for those Tweeting in Japanese. Also, in all markets, when people don’t have to cram their thoughts into 140 characters and actually have some to spare, we see more people Tweeting – which is awesome!

Although we feel confident about our data and the positive impact this change will have, we want to try it out with a small group of people before we make a decision to launch to everyone. What matters most is that this works for our community – we will be collecting data and gathering feedback along the way. We’re hoping fewer Tweets run into the character limit, which should make it easier for everyone to Tweet.

Twitter is about brevity. It’s what makes it such a great way to see what’s happening. Tweets get right to the point with the information or thoughts that matter. That is something we will never change.

We understand since many of you have been Tweeting for years, there may be an emotional attachment to 140 characters – we felt it, too. But we tried this, saw the power of what it will do, and fell in love with this new, still brief, constraint. We are excited to share this today, and we will keep you posted about what we see and what comes next.

Peter Bordes

CEO of Collective audience

Founder & Managing Partner Trajectory Ventures. Lifetime entrepreneur, CEO, Board Member, mentor, advisor and investor.

Obsessed with the infinite realm of possibility in disruptive innovation driving global digital transformation in technology, cloud-based infrastructure, artificial intelligence, data, DevOps, fintech, robotics, aerospace, blockchain and digital media and advertising.