Author: Aubrey Bergauer / California Symphony / Source: Medium

Audience Development: The Long Haul Model

A New Paradigm that Solves the Problems of Audience Attrition, Churn, and Aging

The problems in the orchestra world of declining audiences, aging audiences, and audience turnover have been well articulated, belabored even. In response to these problems, we as a field often talk a lot about incremental gains and successes such as an orchestra that sold 5% more tickets than last year or trimmed expenses enough to balance the budget. Make no mistake, these are big successes under the current model, but when we know as an industry that our fixed costs will continue to rise and outpace the operational tweaks and incremental revenue gains we can achieve, the model needs to be reexamined. This is a post about solutions.

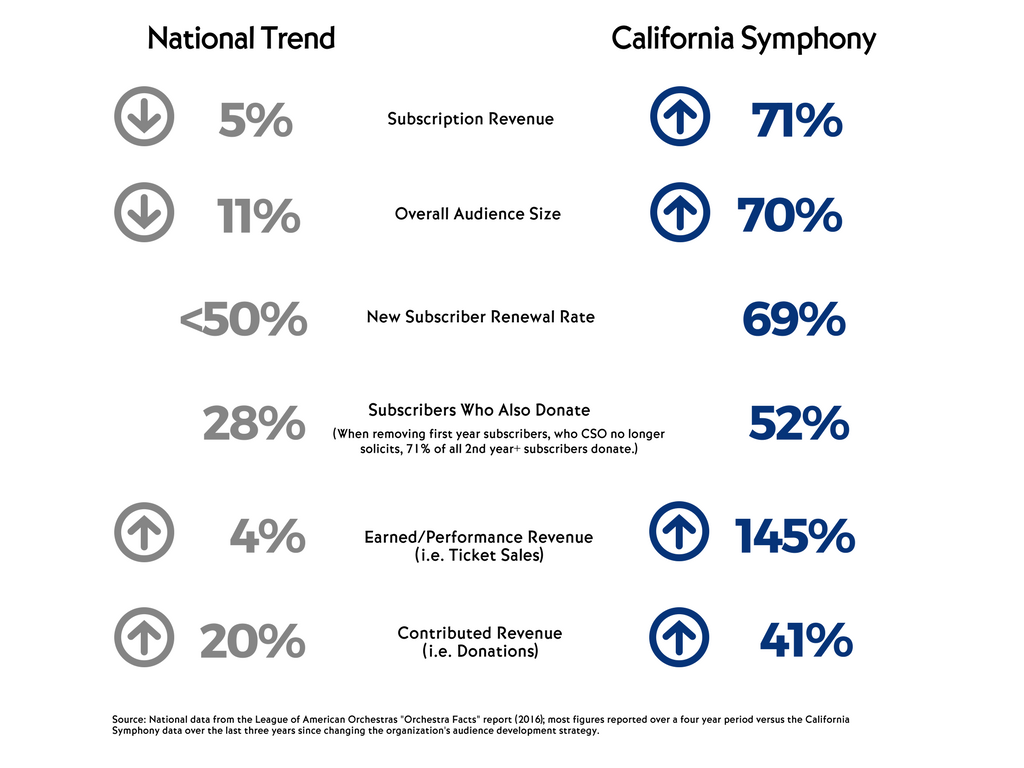

To give away the end of this story, over the last three years, after a calculated change in approach to audience development strategy, the California Symphony has seen profoundly different results from the national trends for orchestras:

This post discusses first what the current/typical audience development model looks like, followed by reasons why organizations do it this way (spoiler alert: there is a long list of explanations in support of the traditional approach, which are barriers to change for many organizations), and ending with counter points on how and why changing the model is worth it, namely because there is big money on the table, which in turn allows us to better serve our mission.

“When we know as an industry that our fixed costs will continue to rise and outpace the operational tweaks and incremental revenue gains we can achieve, the model needs to be reexamined.”

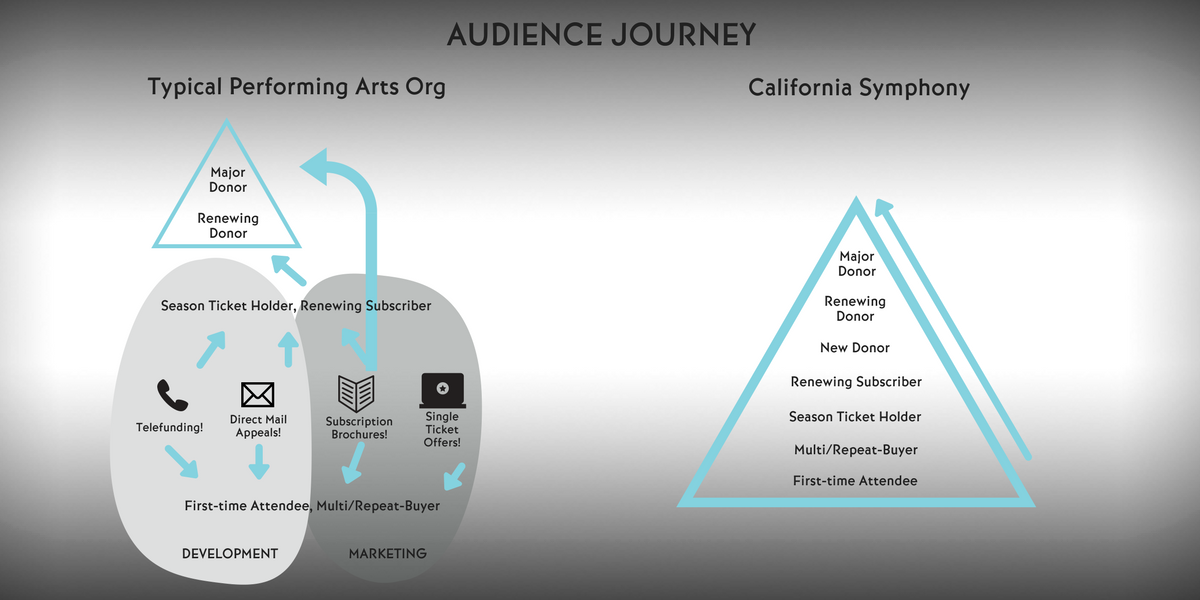

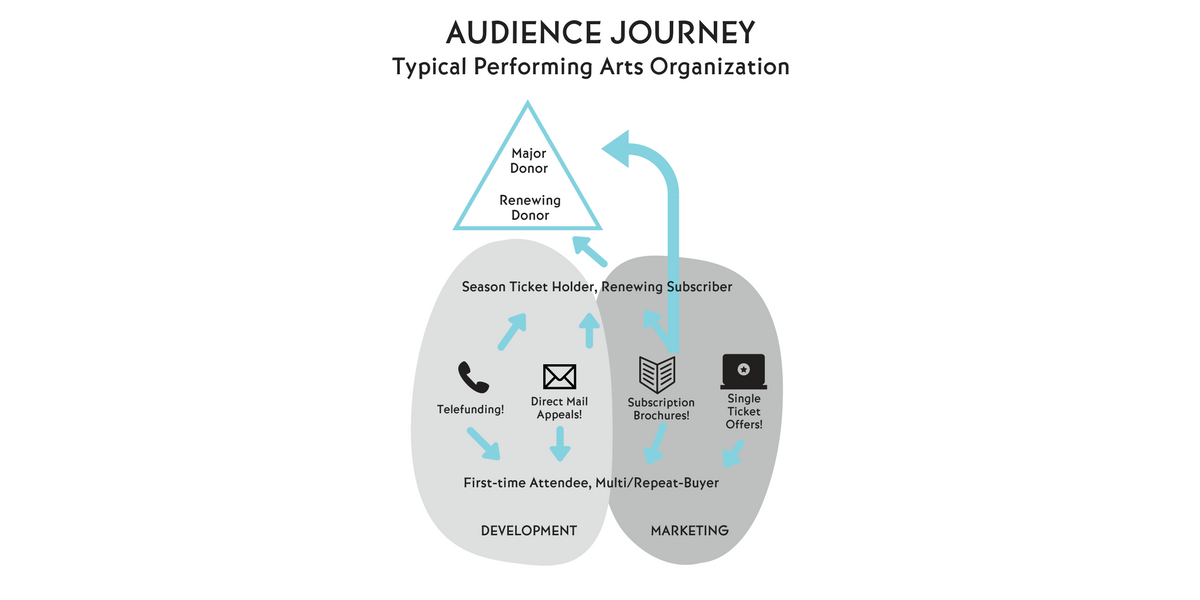

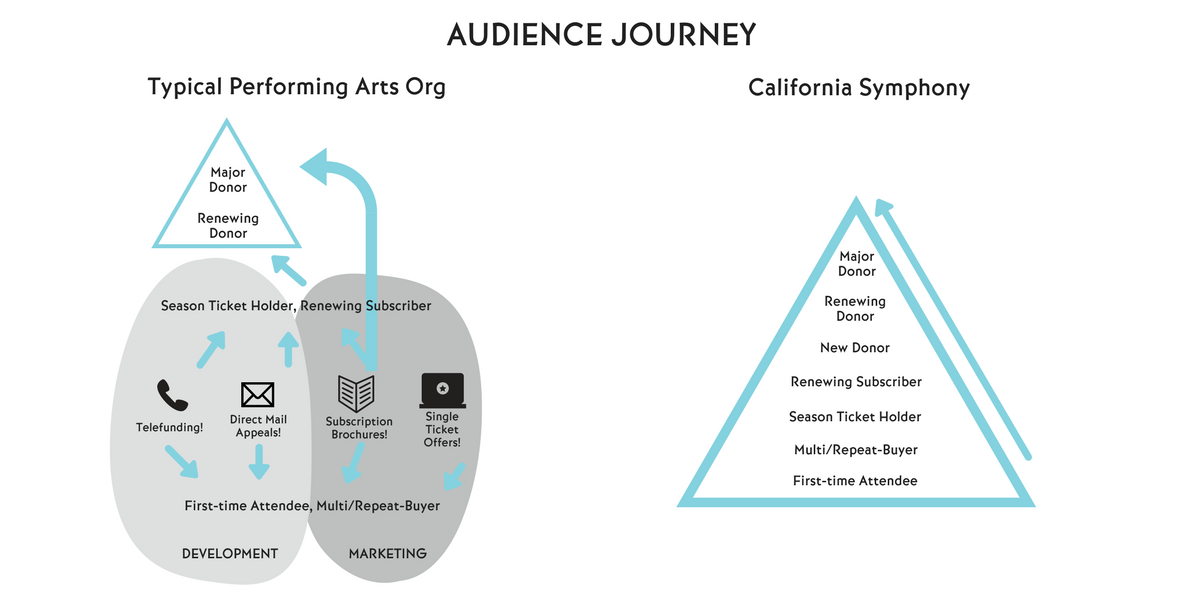

What Audience Development Typically Looks Like

Arts organizations have a lot to offer to our patrons, which is why when a first time attendee comes to a concert, what ensues is essentially a marketing and development free-for-all: that person goes right into all our campaign mailings for subscriptions (“New blood! They came once so they must be willing to at least consider season tickets!”), right to the phone room for telefunding (“They clearly like us enough to attend, so they might be willing to make to a modest donation!”), into all the single ticket marketing efforts like email and online ads (“They completed a purchase on our website, so we are smart and savvy and have that tracking cookie showing them ads everywhere now!”), and into pretty much every direct mail solicitation for single tickets or for donation appeals (“Recent attendance is a great indicator of future engagement!”). That’s a lot of offers and messages…and by a lot I mean a deluge. Then, this same free-for-all takes place again if that person becomes a repeat attendee (“Now they really must be interested in us!”). Then all again if someone takes a chance on a season ticket package, large or small (“They drank the Kool-Aid! They obviously must want to consider donating now!!”). At some point around the time someone becomes a renewing donor or major donor, we sort of get our act together and often have a pretty clear path of next steps for cultivation and stewardship.

To a degree, the current model works. Organizations do make money, and a lot of it, this way. But when 90% of first time buyers don’t come back — a well-documented national stat from Oliver Wyman’s “Churn Study,” made famous by former head of marketing at the Kennedy Center and later Vice President of the League of American Orchestras Jack McAuliffe — this is a problem. And when first year subscribers — a critical group because we know that being a subscriber is the number one indicator of future donation proclivity — are the hardest segment to renew, averaging a 50% or less renewal rate for many organizations, that’s a problem. It’s a giant pipeline problem we have created for ourselves.

What We’ve Done

In short, the California Symphony decided we would do everything we can to create a flowing pipeline. For us, this meant calculated changes to the approach described above, shifting to a strategy focused on patron retention. Now, no matter who you are, whether a first time attendee, or repeat buyer, or new subscriber, or long time donor, or anywhere in between, we have a specific plan for you and a specific next step in mind, and everything we do points you toward that one next step and nothing else. Equally important to what we do now is what we don’t do now, that is to say we do not solicit a donation before a patron is a second year subscriber. (This is usually when jaws drop.) The new approach is a long-term, disciplined strategy, and one that has proven lucrative for us: we’ve grown our audience by a sizable 70% over the last three years — having to add concerts to keep up with the demand — and have nearly quadrupled the number of donor households. We completely reconstructed how we do audience development, and we’re in it for the long haul.

In the latest issue of Symphony magazine (summer 2017), The League of American Orchestras said it best: “Surely, if the military is learning how to become flexible and adapt, orchestras can as well. To do so, they need constantly updated sets of tools and assumptions.” That’s exactly what this is all about.

Why the Industry Does It the Current Way

Earlier this summer, I spoke on this topic — the idea of a focused and strategic audience journey — on a panel at a conference for NPR and public media marketing and development professionals, and during Q&A someone raised their hand and said to me, “Your industry is SO LUCKY to have this research [like the “Churn Study” mentioned above] …so why isn’t everyone doing what you’re doing?” The answer is because change can feel risky, and it turns out, there are several genuine reasons why organizations feel the risk and are reluctant to divert from the traditional model:

1. Revenue attached to old ways. Again, organizations do make money the current way. Some people do subscribe after attending one or two performances, and some people do make a donation when they’re called. And when we are dealing with a pipeline problem, it can be painful to purposefully limit that pipeline at first, such as when you’re pulling a list for a direct mail appeal — let’s say for a fiscal year end campaign when all the low hanging fruit for donations has already made their annual gift — and you know how many more people you could add to that mailing list if you pull recent single ticket buyers. It’s tempting to add those people to the prospect list because some will respond, and those moments make it hard to think about how we’re contributing to that 90% no-return rate because we’re making the wrong ask too soon.

2. Wrong metrics. Another reason change feels risky is because we often measure the wrong things. A bigger database is not the right metric, as an example. Bigger databases do not implicitly mean we are serving more people; a bigger database often means we serve a lot of people once, and that’s bad when our jobs are to cultivate loyal lovers of our art form. In the example above, a larger mailing list is the wrong measure. Looking at the response rate would be a healthier gauge of success (more on that below). Bigger is not always better, and bigger is almost always more expensive (more on that below as well).

“Bigger databases do not implicitly mean we are serving more people; a bigger database often means we serve a lot of people once, and that’s bad when our jobs are to cultivate loyal lovers of our art form.”

3. Short term emphasis. True especially post recession, there is incredible pressure to run our organizations with short-term outcomes. When I was first brought in to the California Symphony to lead a financial turnaround in 2014, one major institutional funder said to me that if we did not immediately have balanced budgets for the next two years, consecutively, then they would pull their funding. And they said this knowing the organization was in crisis and knowing I was implementing a three-year turnaround plan (largely built on the audience journey strategy outlined herein); nonetheless, the directive was firmly to balance the budget in one year. (Side note: we did it, but talk about pressure to NOT take a long-term approach to sustainability!) I pick on that one funder, but the truth is nonprofit leaders see that kind of pressure a lot. Not just from funders, but from watchdog organizations like CharityWatch and GiveWell, etc. And from our boards as well. When the budget does not balance, how often does the board want plans and ideas that promise a quick fix? By the way, if there truly was a quick fix (besides cuts, which are the epitome of a short-sighted solution), wouldn’t we all have implemented that fix a long time ago? The short term pressure is real.

4. No culture for failure. This stems straight from the point above. We all have lean budgets with little to no room for any experimentation to try new things. This isn’t because no one wants to experiment, or find a new model that we all know we need, it’s because we usually must have every penny go toward everything else we’ve committed to do as an organization. We all have top notch artists, quality programming, and education initiatives that make a difference. Failure to fund on any one of these fronts because an experiment did not result in a profitable outcome in its first iteration is not an option. As arts organizations, we need money in an organizational culture with no real appetite for failure — or innovation, or even delayed gratification — because a lot of us simply cannot afford to have a miss.

5. Don’t know how to do it differently. Having siloed departments — particularly siloed marketing and development departments — and a focus on acquisition (both patron and donor acquisition) make it so that our staffs don’t always intuitively know how to do work a different way. We…

Peter Bordes Jr

Founder & Managing Partner Trajectory Ventures. Lifetime entrepreneur, CEO, Board Member, mentor, advisor and investor.

Obsessed with the infinite realm of possibility in disruptive innovation driving global digital transformation in technology, cloud-based infrastructure, artificial intelligence, data, DevOps, fintech, robotics, aerospace, blockchain and digital media and advertising.